Discover Ontario's history as told through its plaques

2004 - Now in our 15th Year - 2019

To find out all about me, you can visit the Home Page

Looking at this page on a smartphone?

For best viewing, hold your phone

in Landscape mode (Horizontal)

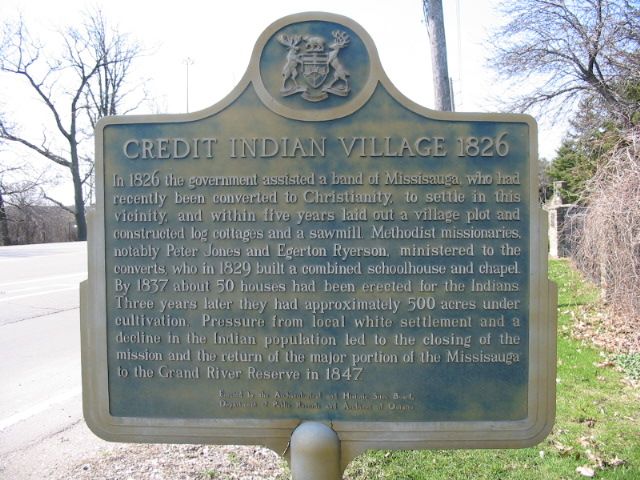

Credit Indian Village 1826

Photo by Alan L Brown - Posted April, 2004

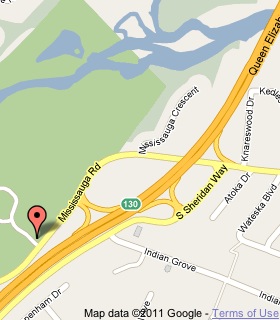

Plaque Location

The Region of Peel

The City of Mississauga

On the east side of Mississauga Road

just north of the Queen Elizabeth Way

beside the entrance to the Mississauga Golf and Country Club

Coordinates: N 43 32.989 W 79 37.214 |

|

Plaque Text

In 1826 the government assisted a band of Mississauga, who had recently been converted to Christianity, to settle in this vicinity, and within five years laid out a village plot and constructed log cottages and a sawmill. Methodist missionaries, notably Peter Jones and Egerton Ryerson, ministered to the converts who in 1829 built a combined schoolhouse and chapel. By 1837 about 50 houses had been erected for the Indians. Three years later they had approximately 200 ha under cultivation. Pressure from local white settlement and a decline in the Indian population led to the closing of the mission and the return of the major portion of the Mississauga to the Grand River Reserve in 1847.

Related Ontario plaques

Crawford Lake Indian Village Site

Credit Indian Village

Cummins Site

The Lawson Site

Newash Indian Village

The Nodwell Indian Village Site

Roebuck Indian Village Site

Upper Gap Archaeological Site

Related Ontario plaques

Reverend Peter Jones 1802-1856

Egerton Ryerson 1803-1882

More

First Nations

Here are the visitors' comments for this page.

> Posted April 18, 2015

This plaque is still missing as of 2015. However, a series of historical markers has been erected not far away in a 'story circle' and heritage garden, about 400 m west of this plaque's former location, on the north side of Mississauga Road (at 43.548102, -79.624430). The partners who created it include the City of Mississauga, Heritage Mississauga, The Erin Mills Development Corp., TD Friends of the Environment Foundation, Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation, and the Community Foundation of Mississauga. Here's what they say. -Wayne

Sacred Garden

For thousands of years, Native peoples have travelled the Credit River Valley. They lived lightly on the land and left little evidence behind to remind us of their presence. This garden is dedicated to the memory of the Our First Nation Ancestors who once lived on this sacred ground. The garden is located on part of what was the Credit Mission Village site, which was home to the Mississaugas of the Credit River circa 1826 to 1847. This site remains culturally and traditionally significant to the Mississaugas of the New Credit today. The plants growing here are representative of traditional indigenous plants that the Mississaugas would have known, and the plaques located around the garden tell, in part, the significant story of the Credit Mission Village.

On This Ground

The Credit Mission, also known as the Credit Indian Village, was located on the site of what is now the Mississaugua [sic] Golf & Country Club. The Credit Mission was part of the Government's plan to settle Native peoples in one area and to allow for new settlement on the surrounding lands. The Mission was built in 1826 under the direction of Reverend Peter Jones (Kahkewaquonaby) and Colonel James Givins, Superintendent of the Indian Department. The village was located on the high grounds overlooking the Credit River. An early description of the village describes "an elevated plateau, cleared of wood, and with three rows of detached cottages, among fields surrounded with rail fences." The village grew to include some 52 family dwellings and an estimated 500 acres were under cultivation.

In addition to the village site, the Mississaugas also had use of land consisting of one mile on each side of the Credit River. From this land they grew grain, hay, apples, potatoes and other root vegetables. They also raised cattle, pigs and other livestock. By the late 1830s, the Credit River Mississaugas had cultivated nearly 900 acres of the 3,000 acre Credit Indian Reserve. In 1838 Eliza Jones, wife of Reverend Peter Jones, wrote: "This little village...is situated on the high and healthy banks of a fine river, whose beautiful flowing waters, well supplied with fish...This village consists of about forty houses; some of these are called log, others frame; each surrounded by half an acre of land, in which the Indians plant every year either potatoes, peas, or Indian corn. In the centre stands, on one side the chapel and school-house, on the other the Mission-house; near which is reserved a lovely spot just on the brow of a sloping bank, sacred to the memory of the dead."

Despite Government misgivings, the Mississaugas proved that the village was a success. They prospered, and early travellers' accounts illustrate the respect for and acknowledgement of what the Mississaugas were accomplishing: "It is gratifying to perceive, that instead of the drunken and savage brawls, happiness and peace have sprung among them, good order, sobriety, and cleanliness in house and person. Their demeanour is moral, their attendance at divine worship regular, and their observance of the church service, grave and attentive."

The Credit Mission thrived for more than a decade. Pressure from surrounding settlement, the loss of title to their traditional lands, and a decline in population led the Mississaugas to relocate to the New Credit Reserve in 1847. The village itself eventually vanished. The meeting lodge, a barn, and a building that was called the chief's residence stood until the 1920s. Since 1906 the property has been home to the Mississaugua Golf and Country Club. Even a portion of Mississauga Road which once ran through the village was realigned, obscuring the original site. However, on a high bank overlooking the river likely remains the cemetery from the Credit Mission.

Voices of Our Ancestors

Thanks in large part to the efforts of Egerton Ryerson, Reverend Peter Jones and his brother John, and Chief Joseph Sawyer, the Methodist faith became established amongst the Mississaugas at the Credit River.

Elected as Chief in 1829, Reverend Peter Jones encouraged the Mississaugas to become "a new race of people", equal to the settlers around them. He sought to establish a firm economic base for the community, to protect the fisheries from encroachment, and to firmly root Christianity and education in the Credit Mission. To this end, the village became home to a Methodist Chapel and to a schoolhouse.

The Credit River Mississaugas' conversion to Christianity involved more than just the adoption of English names, and change came rapidly. The Mississaugas moved from traditional bark structures scattered over a large area to neat log homes, set close together. This meant abandoning communal living. Often three families had lived side-by-side in small clearings, sharing wigwams. With the buildings of the village, two families came to share each log cabin.

The adoption of agriculture provided a new economic base, and men and women acquired new roles. Traditionally men had hunted and fished, while women built the wigwams, dressed skins, cooked, made clothing, tended the children, gathered wood, prepared fires and planted corn. If a warrior had performed any of these tasks, the other men would laugh. But in the changing roles, men put up the log cabins, planted and harvested crops, cut the firewood, and supplied food.

Under the teachings of John Jones, the Mississaugas learned new farming techniques. Once accustomed to harvesting from nature and the traditional uses of indigenous plants, the Mississaugas quickly adjusted to cultivated farms. On their farms, they grew wheat, oats, peas, corn, potatoes and other vegetables, and maintained small orchards. However, the introduction of farming did not altogether cause the Mississaugas to abandon traditional crops and the use of native plants. A common traditional crop planting was known as the Three Sisters, which involved the companion planting of squash, maize (corn), and beans together.

The many indigenous plants found in this garden reflect some of those used for both food and medicine by the Mississaugas. Traditionally harvested food crops included maple syrup, wild rice, strawberries, blueberries, blackberries, wood lilies, giant hyssop, ferns, goosefoot, marsh elder, barley, sumac berries, cranberries, grapes, and varieties of nuts. Wild plants used for their medicinal properties included gaillardia, wild rose, harebell, wild flax, bluestem grass, wild bergamot, wild mint and sage, amongst many others. Tobacco, sage, sweet grass and cedar were considered sacred ceremonial medicines and are still used today.

The Mississaugas also harvested from nature materials needed for building, canoes, baskets, and other items of daily life, and this included gathering wood from red cedar, alder and birch trees. The Mississaugas have left little physical trace of their time on this land.

Who We Are

The Mississaugas, who refer to themselves as Anishinabe, are part of the Algonkian/Algonquin culture. In 1640 Jesuits first recorded a people they referred to as the Oumisagai (Mississaugas), living near the Mississagi River on the northwestern shore of Lake Huron. By the early 1700s they had migrated to the shores of Lake Ontario. Early French and English traders came to refer to all Native peoples on the North shore of Lake Ontario as Chippewa or Ojibwa, of which the Mississaugas were a part.

The name "Mississauga" is believed to mean "River of the North of Many Mouths", although a word in their Native language, "Missisakis", means "Many River Mouths". However, a large portion of the Mississaugas belonged to the Eagle Clan, which was pronounced in their language as "Ma-se-sau-gee".

By the 1720s part of the Mississauga band began to move south and west, following traditional hunting, gathering and fishing practices. The Mississaugas lived lightly on the land, leaving little trace of their presence. As the band travelled they came to a river, which they came to call "Missinihe" ("Trusting Water" - the Credit River), and the established a permanent presence here. The Mississaugas became known for their ability to swiftly carry information over long distances, and were often engaged as messengers. They were also renowned for their swift bark canoes, and their traditional territory included much of what is today Southwestern Ontario.

In the early eighteenth century the Mississaugas traded furs with French traders near the mouths of the Humber and Credit rivers. They traded for everything from buttons, shirts, weapons and ammunition to pots and pans, combs, glasses and axes. After the fall of New France in 1763, the Mississaugas became allied with the English and fought as allies of the British Crown during the American Revolution and the War of 1812.

European settlement began in this area after 1806, and steadily the Mississaugas' practice of freely traversing the land became difficult. Little was done to protect their reserve lands, and the introduction of European diseases such as smallpox and measles claimed two-thirds of their population. By the early 1820s barely 200 Mississaugas remained along the western shore of Lake Ontario.

Disease, along with the decrease of the game and fish populations and the loss of traditional hunting grounds, shook their society. Many warriors, unable to provide for their families, lost their self-esteem and alcohol abuse grew. To survive, the Mississaugas turned to making baskets, brooms, wooden bowls and tools. Influenced by interaction with settlers and Christianity, many adopted new ways and a settled way of life.

We Were Here

In a short period of time the Credit Mission Village grew to include a school, a Methodist chapel, a sawmill, and a meeting lodge. Thanks in large part to the leadership efforts of Reverend Peter Jones (Kahkewaquanaby, 1802-1856), his brother John Jones (Tyantenagen, 1798-1847), Joseph Sawyer (Nawahjegezhegwabe, 1786-1863), John Cameron (Wageezhegome, 1764-1828), and Methodist minister Egerton Ryerson (1803-1882), the Mississaugas prospered for several years.

Much had been accomplished at the Credit Mission by the 1830s. In just 10 years, by their own hard work, the Mississaugas had added a hospital, mechanic's shop, eight barns, and many more houses. They had enclosed 900 acres along the Credit River for pasture and farming.

In 1834 the Credit Harbour Company was formed, with the Mississaugas owning two-thirds of the shares of the company whose primary focus was on developing the natural harbour at the mouth of the Credit River for shipping purposes and warehouses. In 1835 the Mississaugas had a village plot laid out on the west side of the Credit River on the shores of Lake Ontario. The village lots in what would be called Port Credit were sold to incoming settlers.

News of the Credit Mission spread. To raise funds Peter Jones travelled throughout North America and Britain, including having an audience with Queen Victoria in 1838. An Irish clergyman described him as a man of "Saul-like stature, broad shoulders, high cheek bones, erect bearing, sleek jet-black hair, and fine intellect."

In the early 1840s the community had adjusted to the adoption of a new way of life and Christianity, and its population of approximately 250 Mississaugas provided nearly all of their own bread, produce, beef, pork, milk and butter. Traditionally hunters and fishers, in 20 years the Mississaugas had become successful farmers. A few had learned skilled trades, including carpentry and shoemaking. In 1844, Benjamin Slight, a Missionary at the Credit Mission in the 1830s, wrote: "They enjoy domestic comforts, and the blessings of social and civilized life. To contemplate the poor wandering Indian, without home, house, (expecting the wretched wiggewaum [sic]... without means of subsistence... and now to see the contract; the Indian, with his wife and family, in a comfortable cottage, with decent furniture and comfortable provisions in his cellar, barn, & c., must afford conviction to every unprejudiced, sound mind."

However, time was against the Mississaugas and their prosperous village. Vast stretches of forest had been harvested, and the salmon run, once abundant and vital, had almost ceased due to the mills that operated along the Credit River. More and more Mississaugas began to succumb to disease and to pressure from encroaching settlers, and the Crown did not recognize legal land title for the reserve lands. Denied the security of land tenure at the Credit River, a decision was reached in the winter of 1846 to relocate, and over 200 Mississaugas moved in early 1847 to 4,800 acres of land south of Brantford, where they established the New Credit Reserve.

> Posted December 12, 2009

This one has gone missing before, was replaced, now it's gone again. Being next to a busy road, it may have been hit by a plow/car/truck. It could also be the victim of vandalism. I wonder if the Trust is rethinking its location. -Wayne

> Posted November 7, 2008

This plaque is no longer on the site.

Here's where you can send me a comment for this page.

Note: Your email address will be posted at the end of your comment so others can respond to you unless you request otherwise.

Note: Comments are moderated. Yours will appear on this page within 24 hours (usually much sooner).

Note: As soon as I have posted your comment, a reply to your email will be sent informing you.

To send me your comment, click .

Thanks

Alan L Brown

Webmaster

Note: If you wish to send me a personal email, click .